122 people died as a result of the 1863 draft riots. Most of the dead were rioters.

Many of the dead were woman, young boys, and children. The principal cause of death was gunfire.

Among the police and army casualties more than a third were from "friendly" fire.

Thursday, August 15, 2013

New York City's Passion Play

"The Passion Play is a dramatic presentation depicting the Passion of Jesus Christ: his trial, suffering and death [by crucifixion]. It is a traditional part of Lent in several Christian denominations."

Anti-Semitism: "Many Passion Plays historically blamed the Jews for the death of Jesus in a polemical fashion, depicting a crowd of Jewish people condemning Jesus to crucifixion and a Jewish leader assuming eternal collective guilt for the crowd for the murder of Jesus, which...'for centuries prompted vicious attacks — or pogroms — on Europe's Jewish communities.'" This is historically and theologically problematic. Jesus and all of his followers were Jews. Most of the population of Israel at the time had no idea what was going on in Jerusalem. The Roman authorities sentenced Jesus to torture and execution. Theologically blaming the Jews collectively is problematic since the central tenet of Christian tradition is that Christ died to absolve all of mankind for its sins.

The 1863 Draft Riots are New York City's secular version of the Passion Play. It is celebrated in traditional observances by The New York Times (e.g. New York's Mixed Race Riot, http://www.nytimes.com/1997/10/19/opinion/in-america-days-of-terror.html), City University of New York (e.g. Seeing the New York Draft Riots), Hollywood (Gangs of New York), and television (e.g. BBC's Copper seriesBBC Copper Resurrects Five Points). The Times "Disunion" series recently has repeatedly and egregiously positioned the Irish as rioters and rebels, neglecting the immense Irish contribution to saving the Union.

http://hidden-civil-war.blogspot.com/2013/11/the-unions-irish-soldiers-and-sailors.html

In New York's secular Passion Play, the city's African Americans are substituted for Christ and Irish immigrants are saddled with collective guilt for the deaths of New York's black citizens.

The underlying theology for the "secular" New York Passion Play depiction is rooted in the traditional sectarian and ethnic prejudices of Puritan New England and the British Isles.

Like anti-Semitic Passion Plays, the New York version is historically problematic.

-- Manton Marble, Puritan scion, graduate of the University of Rochester

-- Horatio Seymour, Puritan scion, Hobart College and Norwich University, NY Governor

-- George Curtis, Puritan scion, graduate of Harvard

-- August Belmont, German immigrant

-- Nelson Edwards, England

-- Mark Silva, England

Anti-Semitism: "Many Passion Plays historically blamed the Jews for the death of Jesus in a polemical fashion, depicting a crowd of Jewish people condemning Jesus to crucifixion and a Jewish leader assuming eternal collective guilt for the crowd for the murder of Jesus, which...'for centuries prompted vicious attacks — or pogroms — on Europe's Jewish communities.'" This is historically and theologically problematic. Jesus and all of his followers were Jews. Most of the population of Israel at the time had no idea what was going on in Jerusalem. The Roman authorities sentenced Jesus to torture and execution. Theologically blaming the Jews collectively is problematic since the central tenet of Christian tradition is that Christ died to absolve all of mankind for its sins.

The 1863 Draft Riots are New York City's secular version of the Passion Play. It is celebrated in traditional observances by The New York Times (e.g. New York's Mixed Race Riot, http://www.nytimes.com/1997/10/19/opinion/in-america-days-of-terror.html), City University of New York (e.g. Seeing the New York Draft Riots), Hollywood (Gangs of New York), and television (e.g. BBC's Copper seriesBBC Copper Resurrects Five Points). The Times "Disunion" series recently has repeatedly and egregiously positioned the Irish as rioters and rebels, neglecting the immense Irish contribution to saving the Union.

http://hidden-civil-war.blogspot.com/2013/11/the-unions-irish-soldiers-and-sailors.html

In New York's secular Passion Play, the city's African Americans are substituted for Christ and Irish immigrants are saddled with collective guilt for the deaths of New York's black citizens.

The underlying theology for the "secular" New York Passion Play depiction is rooted in the traditional sectarian and ethnic prejudices of Puritan New England and the British Isles.

Like anti-Semitic Passion Plays, the New York version is historically problematic.

- The overwhelming majority of the 122 riot dead were "rioters", mostly shot by the army.

- Although many of those arrested during the riots had Irish names, the majority of the 400 arrested didn't.

- Most of the riot deaths occurred north of 14th street. Below 14th street, 8 of the 16 deaths were clustered in Little Germany's 11th Ward. Draft Riot Death Map

- The overwhelming majority of the city's population didn't riot, including its Irish immigrants (i.e., there were no riot deaths in the "Irish" 6th Ward, or the 14th Ward, home of Old St. Patrick's Cathedral).

- No units from the Gettysburg fighting or the Army of the Potomac were sent to New York City to put down the riots. None, zero, nada. A few militia regiments were returned to the city from the defenses of Harrisburg, PA, but by the time they arrived most of the trouble had subsided.

- The largest riot crowd (5000+) gathered at Old St. Patrick's Cathedral in the 14th Ward. This was a non-violent gathering called by Archbishop Hughes to condemn violence in the city.

- Most of the police who fought the rioters were Irish

- New York City was a victim of its own loyalties. The Great Militia Mobilization of 1863 stripped the city of self-defense militia (15,000+ strong), leaving it without the overwhelming force it normally had on hand to preempt wanton rioting.

- New York State sent 27 militia regiments to defend Pennsylvania in June of 1863. 20 came from New York City. No other state sent their militia to help Pennsylvania, except for one from New Jersey.

- New York City was overwhelmingly loyal to the Union, despite efforts of commercial interests connected to the South. The city provided 200,000 soldiers and sailors to the Union cause. 20,000 of them died during the war. 200+ of the city's soldiers and sailors were awarded the Medal of Honor. Most of the soldiers were immigrants and by far the largest group were Irish.

- New York City units fought valiantly throughout the war despite horrific losses, before and after Emancipation. The city's Irish Brigade is a storied unit that gave Notre Dame University a nickname (carried there by its chaplains), but it's a small part of the story. Immigrants in the city's German Ranger regiment died at Spotsylvania and the Wilderness in horrible numbers. Irish immigrants who were turned away at Boston, enlisted at New York instead, forming the core of the 40th New York Volunteers. The 40th had over 200 casualties during the Peninsula battles in 1862, 123 at Fredericksburg on the eve of Emancipation, 150 at Gettysburg, and long after Emancipation over 300 casualties in 1864 in the Spotsylvania and Wilderness fighting, by then it had been reinforced with the survivors from other city regiments, notably the 37th New York Irish Rifles. Patrick Doherty survived capture at Bull Run to lead the 16th New York when it hunted down John Wilkes Booth after the assassination of Lincoln. Doherty's funeral in 1897 was held at my family's church, St. Charles Boromeo, in Harlem.

- The principal instigators and many riot leaders weren't Irish:

-- Manton Marble, Puritan scion, graduate of the University of Rochester

-- Horatio Seymour, Puritan scion, Hobart College and Norwich University, NY Governor

-- George Curtis, Puritan scion, graduate of Harvard

-- August Belmont, German immigrant

Belmont was national leader for the Democrats and an in-law of John Slidell.

Slidell, Columbia educated, New York born with Scots roots, Confederate ambassador

-- Richard Sears McCulloh, scion of an old Scots Protestant Maryland family,

graduate of Princeton,

Columbia University professor of chemistry at Columbia University at the time of the riots

Possibly the riots principal arsonist. Turned up in Richmond after the riots,

offering to make weapons of mass destruction for the Confederacy.

-- John Andrews, VIRGINIA-- Nelson Edwards, England

-- Mark Silva, England

- Ivy League historians are better at remembering the alleged sins of immigrants than the immense economic and cultural connect between their institutions and slavery and the Confederacy. http://hidden-civil-war.blogspot.com/2014/05/ivy-league-confederates-harvard-and.html

Wednesday, August 14, 2013

The Catholic Priest Who Owned His Own Family

"We are neither Jew nor Gentile, slave nor free, but all one in Christ."

-- James Healy, Bishop of Portland

James Augustine Healy has the distinction of being the first valedictorian of Holy Cross College at Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1849. He was also America's first Catholic priest and bishop of African descent.

Healy also had the dubious distinction of owning his own family after his father died in 1850. First, his brother Hugh went to their father's plantation in Georgia, and spirited the younger Healy children out of the state to avoid their enslavement. James then had to negotiate through a family friend the placement of his father's slaves with sympathetic farmers, Georgia laws making emancipation at the time highly problematic. The Healy children themselves were in a dangerous predicament due to the passions of that era and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, but safe enough in Massachusetts. Their mother is believed to have died before their father, but her death may have been a ruse to shield her from Georgia law.

Healy's father was an Irish immigrant who married one of his slaves, the beautiful and smart Eliza Mary. He'd been attracted to Georgia by the expanding cotton economy and the opportunity to pioneer the Georgia frontier. Michael and Eliza's children found their way to Massachusetts by another coincidence of immigration and economic expansion.

Tobias Boland was a young Irishman who learned canal building in England and immigrated to America to work on the Erie Canal. He became a successful contractor who built the Blackstone Canal connecting Worcester and Providence, Rhode Island, and later the Boston and Worcester and other railroads. Influenced by his Catholic faith and his first and second wives, Boland underwrote the founding of Holy Cross College at Worcester. Worcester became the first site for a Catholic college in New England primarily to avoid Boston where anti-Catholic sentiment, inflamed by the preaching of Lyman Beecher, led to the burning of the Ursuline Convent in 1834. When planter Michael Morris Healy, looking for a school for his children whose schooling was prohibited by Georgia law, encountered some Jesuits in his travels, they recommended the new school at Worcester. James Healy would spend his first Christmas in New England, and many others, with the Boland family.

James Healy was joined in Worcester by his brother Patrick who became a Jesuit priest and a famous president of Georgetown University. Younger brother Michael followed them to Worcester, but chose a vocation at sea, not with the church. He was commissioned an officer in the Revenue Cutter Service by President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War and had a heroically famous career in Alaska, celebrated by James Michener in an historical novel of the same name, his battles with poachers an inspiration for Jack London's The Sea Wolf.

-- James Healy, Bishop of Portland

James Augustine Healy has the distinction of being the first valedictorian of Holy Cross College at Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1849. He was also America's first Catholic priest and bishop of African descent.

Healy also had the dubious distinction of owning his own family after his father died in 1850. First, his brother Hugh went to their father's plantation in Georgia, and spirited the younger Healy children out of the state to avoid their enslavement. James then had to negotiate through a family friend the placement of his father's slaves with sympathetic farmers, Georgia laws making emancipation at the time highly problematic. The Healy children themselves were in a dangerous predicament due to the passions of that era and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, but safe enough in Massachusetts. Their mother is believed to have died before their father, but her death may have been a ruse to shield her from Georgia law.

Healy's father was an Irish immigrant who married one of his slaves, the beautiful and smart Eliza Mary. He'd been attracted to Georgia by the expanding cotton economy and the opportunity to pioneer the Georgia frontier. Michael and Eliza's children found their way to Massachusetts by another coincidence of immigration and economic expansion.

Tobias Boland was a young Irishman who learned canal building in England and immigrated to America to work on the Erie Canal. He became a successful contractor who built the Blackstone Canal connecting Worcester and Providence, Rhode Island, and later the Boston and Worcester and other railroads. Influenced by his Catholic faith and his first and second wives, Boland underwrote the founding of Holy Cross College at Worcester. Worcester became the first site for a Catholic college in New England primarily to avoid Boston where anti-Catholic sentiment, inflamed by the preaching of Lyman Beecher, led to the burning of the Ursuline Convent in 1834. When planter Michael Morris Healy, looking for a school for his children whose schooling was prohibited by Georgia law, encountered some Jesuits in his travels, they recommended the new school at Worcester. James Healy would spend his first Christmas in New England, and many others, with the Boland family.

James Healy was joined in Worcester by his brother Patrick who became a Jesuit priest and a famous president of Georgetown University. Younger brother Michael followed them to Worcester, but chose a vocation at sea, not with the church. He was commissioned an officer in the Revenue Cutter Service by President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War and had a heroically famous career in Alaska, celebrated by James Michener in an historical novel of the same name, his battles with poachers an inspiration for Jack London's The Sea Wolf.

* * * * * * * * *

The challenge for the Healys was avoiding trouble because of their mother's race. They had to avoid the specter of their own enslavement during the Fugitive Slave Law years, especially of their young brothers and sisters still living on the Georgia plantation when their father died. Even though Sherwood and Bishop James Healy's mixed heritage was widely known in Maine, among America's black community and while they held prominent clerical positions in Boston before and after the Civil War, the Healy's and the Society of Jesus managed to keep this from being an issue, especially while Patrick was president at Georgetown. Michael Healy's heritage haunted him at Holy Cross and then while commanding the Revenue Cutter Bear in Alaskan waters.

Monday, August 12, 2013

The Generals and a Small Catholic Church in Ohio

Saint Joseph's was the first Catholic Church in Ohio, founded at Somerset by Edward Fenwick, a Dominican priest, on land donated by Jacob Dittoe. On Sunday's in the 1830s you would find a redheaded boy attending services there along with his foster brothers and sisters of the Ewing family and the small children of John and Mary Sheridan. Five of the congregation's children would become famous Union army generals.

Major General Hugh Boyle Ewing, commanded the 30th Ohio and Scammon's Brigade at Antietam, and the 4th Division of XV Corps during the assault on Missionary Ridge at Chattanooga. Post-war: Minister to Holland

Major General Thomas Ewing, Jr., commanded the 11th Kansas regiment, promoted to general after the battle of Prairie Grove, led the defense of Fort Davidson at Pilot's Knob against Sterling Price's invasion of Missouri in 1864. Issued General Order No. 11 after the Quantrill massacre at Leavenworth, Kansas, expelling Confederate sympathizers from western Missouri.

Post-war: defended Dr. Samuel Mudd, Samuel Arnold and Edmund Spangler during the Lincoln conspiracy trials. Prevailed on his 11th Kansas comrade Senator Edmund Ross to vote against the Johnson impeachment. Congressman from Ohio.

Brigadier General Charles Ewing, severely wounded at Vicksburg, promoted for gallant conduct at Missionary Ridge and during the Atlanta campaign.

Post-war: Catholic Commissioner for the Indian Missions.

General of the Army of the United States William Tecumseh Sherman, commanded Union troops from Bull Run through the surrender of the Confederacy. Led the Union armies that prevailed during the Atlanta, Savannah ("The March to the Sea") and Carolinas campaigns.

Garrison Frazier, a Baptist minister, declared in response to an inquiry about the feelings of the black community:

Post-war: Commanding General of the United States Army.

Famous quote: "War is Hell."

General of the Army of the United States Phillip Sheridan, personally led his division to the top of Missionary Ridge during the Battle of Chattanooga. Commanded the Union army cavalry during the Overland Campaign, when his troops killed J.E.B. Stuart at Yellow Tavern. Commanded the Army of the Shenandoah in its victories at Winchester and Cedar Creek. Cut off the Confederate retreat from Richmond at the Battle of Sayler's Creek forcing Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox.

Post-war: Commanded the Union forces that pacified Texas and Louisiana, aiding Benito Juarez in the expulsion of the French from Mexico. Removed from command by President Johnson for "overzealously" enforcing Reconstruction. Commanding General of the United States Army who vigorously supported the establishment and protection of Yellowstone Park.

Famous quote: "If I owned Texas and Hell, I'd rent out Texas and live in Hell."

Major General Hugh Boyle Ewing, commanded the 30th Ohio and Scammon's Brigade at Antietam, and the 4th Division of XV Corps during the assault on Missionary Ridge at Chattanooga. Post-war: Minister to Holland

Major General Thomas Ewing, Jr., commanded the 11th Kansas regiment, promoted to general after the battle of Prairie Grove, led the defense of Fort Davidson at Pilot's Knob against Sterling Price's invasion of Missouri in 1864. Issued General Order No. 11 after the Quantrill massacre at Leavenworth, Kansas, expelling Confederate sympathizers from western Missouri.

Post-war: defended Dr. Samuel Mudd, Samuel Arnold and Edmund Spangler during the Lincoln conspiracy trials. Prevailed on his 11th Kansas comrade Senator Edmund Ross to vote against the Johnson impeachment. Congressman from Ohio.

Brigadier General Charles Ewing, severely wounded at Vicksburg, promoted for gallant conduct at Missionary Ridge and during the Atlanta campaign.

Post-war: Catholic Commissioner for the Indian Missions.

General of the Army of the United States William Tecumseh Sherman, commanded Union troops from Bull Run through the surrender of the Confederacy. Led the Union armies that prevailed during the Atlanta, Savannah ("The March to the Sea") and Carolinas campaigns.

My aim then was to whip the rebels, to humble their pride, to follow them to their inmost recesses, and make them fear and dread us. "Fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom." I did not want them to cast in our teeth what General Hood had once done at Atlanta, that we had to call on their slaves to help us to subdue them. But, as regards kindness to the race ... I assert that no army ever did more for that race than the one I commanded at Savannah.

Garrison Frazier, a Baptist minister, declared in response to an inquiry about the feelings of the black community:

Four days later, Sherman issued his Special Field Order No. 15. The orders provided for the settlement of 40,000 freed slaves and black refugees on land expropriated from white landowners in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.We looked upon General Sherman, prior to his arrival, as a man, in the providence of God, specially set apart to accomplish this work, and we unanimously felt inexpressible gratitude to him, looking upon him as a man that should be honored for the faithful performance of his duty. Some of us called upon him immediately upon his arrival, and it is probable he did not meet [Secretary Stanton] with more courtesy than he met us. His conduct and deportment toward us characterized him as a friend and a gentleman.

Post-war: Commanding General of the United States Army.

Famous quote: "War is Hell."

General of the Army of the United States Phillip Sheridan, personally led his division to the top of Missionary Ridge during the Battle of Chattanooga. Commanded the Union army cavalry during the Overland Campaign, when his troops killed J.E.B. Stuart at Yellow Tavern. Commanded the Army of the Shenandoah in its victories at Winchester and Cedar Creek. Cut off the Confederate retreat from Richmond at the Battle of Sayler's Creek forcing Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox.

Post-war: Commanded the Union forces that pacified Texas and Louisiana, aiding Benito Juarez in the expulsion of the French from Mexico. Removed from command by President Johnson for "overzealously" enforcing Reconstruction. Commanding General of the United States Army who vigorously supported the establishment and protection of Yellowstone Park.

Famous quote: "If I owned Texas and Hell, I'd rent out Texas and live in Hell."

The Catholic Nun Who Was Sherman's Aunt

Mother Angela Gillespie in addition to her contributions to education of women and the welfare of Civil War soldiers was the aunt (or cousin?) of Ellen Ewing, the wife of William Tecumseh Sherman. During the Civil War, Ellen Ewing and her children resided with her aunt at Notre Dame and were visited on at least one occasion by the great general.

Gillespie took the habit and the name Sister Mary of St. Angela in April 1853 and was sent to the order’s novitiate in Caen, France. After taking her final vows in December, she returned to Bertrand as director of studies of St. Mary’s Academy, and in April 1854 she became superior of the convent. In 1855 St. Mary’s Academy was moved to a new site near Notre Dame and became St. Mary’s College. A believer in full educational opportunities for women, Mother Angela instituted courses in advanced mathematics, the sciences, modern foreign languages, philosophy, theology, art, and music. By 1856 nuns of the Holy Cross order were teaching in parochial schools in Chicago, and in 1858 the order established St. Angela’s Academy in Morris, Illinois. In 1860 Mother Angela began publishing a graded series of Metropolitan Readers for use in elementary through college-level courses. From 1866 she was largely responsible for editing Ave Maria, a Catholic periodical founded by Father Sorin.

In October 1861 Mother Angela offered the nursing services of the order to General Ulysses S. Grant. Within a short time, Holy Cross sisters were employed in army hospitals in Paducah and Louisville, Kentucky, and they later worked in Cairo, Illinois, in Memphis, Tennessee, in Washington, D.C., and elsewhere, as well as aboard hospital ships on the Mississippi River. The order’s main efforts went into the conversion of a row of riverfront warehouses in Mound City, Illinois, into a clean and efficient 1,500-bed military hospital.

The expansion of the order and of its educational work proceeded rapidly under Mother Angela’s direction. Among the 45 institutions founded by the order between 1855 and 1882 were St. Mary’s Academy in Austin, Texas (1874), St. Catherine’s Normal Institute in Baltimore, Maryland (1875), St. Mary of the Assumption in Salt Lake City, Utah (1875), and Holy Cross Academy in Washington, D.C. (1878). In 1869 difficulties between the American and French branches of the order led to the establishment of the American branch on an independent basis, with Mother Angela as provincial superior under the authority of Father Sorin as superior. Although she had been preceded by two mothers superior, Mother Angela was established as the effective founder of the order in the United States.

Source: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/233751/Mother-Angela-Gillespie

http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/pers-us/uspers-g/a-gillsp.htm

* * * * *

Mother Angela Gillespie, original name Eliza Maria Gillespie (born Feb. 21, 1824, near Brownsville, Pa., U.S.—died March 4, 1887, South Bend, Ind.), American religious leader who guided her order in dramatically expanding higher education for women by founding numerous institutions throughout the United States.

Eliza Maria Gillespie was educated at girls’ schools in her native town and, in 1836–38, in Somerset, Ohio. In the latter year she moved with her widowed mother to Lancaster, Ohio. In 1840 she entered the Visitation Academy in Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), graduating in 1842. She returned to Lancaster for nine years, busying herself with charitable work, and from 1847 to 1851 taught in a parish school. During 1851–53 she taught at St. Mary’s Seminary, a nondenominational, state-supported school in St. Mary’s City, Maryland. Her long-standing inclination toward the religious life culminated in her decision in January 1853 to enter the Sisters of Mercy convent in Chicago. On her way there she stopped to visit her brother, a seminarian at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana. She met Father Edward F. Sorin, founder of the university, who influenced her to join the Sisters of the Holy Cross, a French order with a convent at Bertrand, Michigan.Gillespie took the habit and the name Sister Mary of St. Angela in April 1853 and was sent to the order’s novitiate in Caen, France. After taking her final vows in December, she returned to Bertrand as director of studies of St. Mary’s Academy, and in April 1854 she became superior of the convent. In 1855 St. Mary’s Academy was moved to a new site near Notre Dame and became St. Mary’s College. A believer in full educational opportunities for women, Mother Angela instituted courses in advanced mathematics, the sciences, modern foreign languages, philosophy, theology, art, and music. By 1856 nuns of the Holy Cross order were teaching in parochial schools in Chicago, and in 1858 the order established St. Angela’s Academy in Morris, Illinois. In 1860 Mother Angela began publishing a graded series of Metropolitan Readers for use in elementary through college-level courses. From 1866 she was largely responsible for editing Ave Maria, a Catholic periodical founded by Father Sorin.

In October 1861 Mother Angela offered the nursing services of the order to General Ulysses S. Grant. Within a short time, Holy Cross sisters were employed in army hospitals in Paducah and Louisville, Kentucky, and they later worked in Cairo, Illinois, in Memphis, Tennessee, in Washington, D.C., and elsewhere, as well as aboard hospital ships on the Mississippi River. The order’s main efforts went into the conversion of a row of riverfront warehouses in Mound City, Illinois, into a clean and efficient 1,500-bed military hospital.

The expansion of the order and of its educational work proceeded rapidly under Mother Angela’s direction. Among the 45 institutions founded by the order between 1855 and 1882 were St. Mary’s Academy in Austin, Texas (1874), St. Catherine’s Normal Institute in Baltimore, Maryland (1875), St. Mary of the Assumption in Salt Lake City, Utah (1875), and Holy Cross Academy in Washington, D.C. (1878). In 1869 difficulties between the American and French branches of the order led to the establishment of the American branch on an independent basis, with Mother Angela as provincial superior under the authority of Father Sorin as superior. Although she had been preceded by two mothers superior, Mother Angela was established as the effective founder of the order in the United States.

Source: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/233751/Mother-Angela-Gillespie

http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/pers-us/uspers-g/a-gillsp.htm

Sunday, August 11, 2013

The North's Greatest Hispanic General

He commanded the Union army that defeated Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg in 1863, working a miracle to bring the full strength of the Army of the Potomac into the battle by forced marches, while Lee continued to attack unwilling to concede that he was outmaneuvered and outnumbered.

George Gordon Meade was born to a Catholic family at Cadiz, Spain. He was a native Spanish speaker, lived in Spain until he was a teenager and was sent to America to attend school and West Point. His first assignment upon graduation was to assist in surveying the route for the Long Island Railroad.

But wait! There's more! Meade's history is more complicated still. His ancestors left Kinsale, Ireland, when their lands were forfeited in the 17th century by British anti-Catholic Penal Laws following the "Glorious Revolution." After a stop in France the Meades ended up in the Barbados where they prospered and became slave holders, owning "a plantation of 140 acres in St. John's Parish with 68 negro slaves." Eventually the Meades moved to Philadelphia:

George Gordon Meade was born to a Catholic family at Cadiz, Spain. He was a native Spanish speaker, lived in Spain until he was a teenager and was sent to America to attend school and West Point. His first assignment upon graduation was to assist in surveying the route for the Long Island Railroad.

But wait! There's more! Meade's history is more complicated still. His ancestors left Kinsale, Ireland, when their lands were forfeited in the 17th century by British anti-Catholic Penal Laws following the "Glorious Revolution." After a stop in France the Meades ended up in the Barbados where they prospered and became slave holders, owning "a plantation of 140 acres in St. John's Parish with 68 negro slaves." Eventually the Meades moved to Philadelphia:

"Gen. MEADE, the new leader of the Army of the Potomac, is the grandson of GEORGE MEADE, of Philadelphia, an eminent Irish-American merchant, whose firm (MEADE & FITZSIMMONS) contributed in 1781 $10,000 to a fund for the relief of the famishing army of Gen. WASHINGTON." -- New York Times, July 2, 1863

Apparently, the Irish saved the Union twice.

Balance Due -- Union Defence Committee, NYC

Mayor's Office, New York, February 12, 1885

Hon. Edward V. Lowe, Comptroller

Dear Sir:

On the 22nd of April, 1861, the Mayor, Aldermen and Commonalty of the City of New York, in Common Council convened, adopted an ordinance appropriating one million dollars ($1,000,000) for the purpose of procuring the necessary equipments and outfits of soldiers who enlisted in the service of the State under a requisition by the President of the United States, and for aid and support of their families.

This sum was disbursed by the "Union Defence Committee of the City of New York," which consisted of the Mayor and other officials and a number of prominent citizens.

The General Government [federal], of this sum, repaid:

On October 19,1861...... $66,793.25

On May 12, 1862........... $40,215.50

Leaving a balance due...$892,991.25

Which with accumulations of interest will make a large sum which should be restored to the City Treasury.

I am informed that the Board of Alderman in 1866 and again in 1869 memorialized Congress with a view to legislation on the subject.

I desire to be put in possession of all the facts in possession of your department, to the end that I may recommend to the Board of Alderman such appropriate action as may be advisable to secure repayment of the balance due to the city.

The Government has reimbursed all advances, I believe, to the several State governments, and may do so in this instance with a municipal government.

Yours respectfully

W. R. Grace

Mayor

* * * * *

To date New York City has never been reimbursed for its contributions in defense of the Union.

Hon. Edward V. Lowe, Comptroller

Dear Sir:

On the 22nd of April, 1861, the Mayor, Aldermen and Commonalty of the City of New York, in Common Council convened, adopted an ordinance appropriating one million dollars ($1,000,000) for the purpose of procuring the necessary equipments and outfits of soldiers who enlisted in the service of the State under a requisition by the President of the United States, and for aid and support of their families.

This sum was disbursed by the "Union Defence Committee of the City of New York," which consisted of the Mayor and other officials and a number of prominent citizens.

The General Government [federal], of this sum, repaid:

On October 19,1861...... $66,793.25

On May 12, 1862........... $40,215.50

Leaving a balance due...$892,991.25

Which with accumulations of interest will make a large sum which should be restored to the City Treasury.

I am informed that the Board of Alderman in 1866 and again in 1869 memorialized Congress with a view to legislation on the subject.

I desire to be put in possession of all the facts in possession of your department, to the end that I may recommend to the Board of Alderman such appropriate action as may be advisable to secure repayment of the balance due to the city.

The Government has reimbursed all advances, I believe, to the several State governments, and may do so in this instance with a municipal government.

Yours respectfully

W. R. Grace

Mayor

* * * * *

To date New York City has never been reimbursed for its contributions in defense of the Union.

Saturday, August 10, 2013

Regattas 1864

In the summer of 1864, young Americans, many German and Irish immigrants from New York City, were dying by the thousands in Virginia's Wilderness, at Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor and the siege of Petersburg, earning Grant the nickname "Butcher." What were America's elites doing, the "flower of Yale and Harvard"? Organizing regattas and sporting events to "display their manly vigor."

* * * * *

From the New York Times, July 1864:

Harvard assembled, and there were large accessions of representatives from Amherst, Williams, Brown, and other colleges. Many distinguished citizens were present to witness the athletic sports, and they could not fail to be impressed with the character and manly vigor of their successors in scientific, business, political and social prominence.

sufficiently elevated to command an admirable view of the course. Seats had been arranged in favorable positions, and thousands of spectators were gathered, choosing situations from the judge's boat a mile or more alone the shore on either side. The Worcester Cornet Band

discoursed music at intervals during the races.

* * * * *

From the New York Times, July 1864:

The great aquatic contest between Harvard and Yale for the championship and a set of colors, which took place yesterday at Worcester, called together a very large number of students, gymnasts and amateur boatmen.

A finer looking set of young men rarely congregate in a New-England city or town -- as the

young ladies of Worcester would no doubt bear willing testimony. The flower of Yale andHarvard assembled, and there were large accessions of representatives from Amherst, Williams, Brown, and other colleges. Many distinguished citizens were present to witness the athletic sports, and they could not fail to be impressed with the character and manly vigor of their successors in scientific, business, political and social prominence.

The scene of the regatta was Lake Quinsigamond, a charming sheet of water about two miles

from Worcester. The banks of the pond are well wooded, affording ample shade, and aresufficiently elevated to command an admirable view of the course. Seats had been arranged in favorable positions, and thousands of spectators were gathered, choosing situations from the judge's boat a mile or more alone the shore on either side. The Worcester Cornet Band

discoursed music at intervals during the races.

The second and most important race, deciding the championship, followed immediately. The Harvard crew is supposed to comprise the best oarsmen in college.

The crews were:

Harvard -- Horatio G. Curtis (stroke,) Robert S. Peabody, Thomas Nelson, John Greenough,

Edward C. Perkins, Edwin Farnham, (bow,) Costume -- white shirts, red handkerchiefs.

Yale -- W.R. Bacon, (stroke,) M.W. Seymour, Louie Stozkotf, E.B. Bennett, E.D. Coffin, Jr.,

W.W. Scranton, (bow.) Costume -- flesh-colored shirts, blue handkerchiefs.

* * * * *

Killed in action:

Colonel Richard Byrnes, Commander Irish Brigade, KIA Cold Harbor,

born County Caven, Ireland, buried Calvary Cemetery, New York City

Colonel Patrick Kelly, Commander Irish Brigade, KIA Petersburg,

born County Galway, Ireland, buried Calvary Cemetery, New York City

Lt. Count Van Haake, 52th New York, German Rangers, KIA Spotsylvania

Lt. Baron Von Steuben, 52th New York, German Rangers, KIA Spotsylvania

Major Thomas Tuohy, Irish Brigade, KIA Wilderness,

buried Calvary Cemetery, New York City

Colonel James McMahon, Commander 164th NY, Corcoran's Irish Legion,

KIA Cold Harbor.

buried Calvary Cemetery, New York City

Colonel James McMahon, Commander 164th NY, Corcoran's Irish Legion,

KIA Cold Harbor.

* * * * *

Edmund Coffin of the Yale crew went on to Columbia Law school and became a prominent New York City lawyer and ancestor of Yale chaplain, William Sloane Coffin.

Riots and Regattas

"Society is divided into two classes -- producers and non-producers." The former were poor; the latter the rich who "amassed their wealth from the products of the other classes." The war fell disproportionately on the sons of the laboring class. The rich made few sacrifices and further exploited white workers by backing the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in order to "flood the North" with inexpensive blacks, "many of them mechanics," rather than paying whites "at customary wages." -- Fernando (Lehmann) Wood

What were the North's elites doing to prove that they were as committed to waging war on the South as working class Americans. As the Confederate army marched north into Pennsylvania in June of 1863 on the way to the cataclysmic battle at Gettysburg, the North's elite's were organizing regattas, as if there wasn't a care in the world.

* * * * *

The Annual Regatta of the Jersey City Yacht Club came off Tuesday afternoon, at 1 o'clock, from McGiehan's Basin, foot of Van Vorst-street, a large number of spectators being present.

ground of the New-York club, Hoboken.

of Kentucky, the owner of Idlewild and other fast horses, now at his racing stables adjoining the course.

-- NYT, 6/23/1863

Mr. STAPHEN FLEMING, of Pittsburgh, Mr. HAMMILL's backer, offered

morning, an Albany gentleman offered to bet $800 even on HAMMILL., and was snapped up by a Poughkeepsian; and we had it for a fact that Mr. FLEMING had deposited $20,000 in the banks, a great portion of which he invested on HAMMILE. The crowds on the docks and in the steamboat hotel were immense, two propellers having come from Newburgh loaded with passengers, and a small one from Cornwall with WARD and his immediate friends. He lives, and trained himself at Cornwall, which accounts for his fine condition.

advantage to him, but the water in this race was as smooth as glass.

What were the North's elites doing to prove that they were as committed to waging war on the South as working class Americans. As the Confederate army marched north into Pennsylvania in June of 1863 on the way to the cataclysmic battle at Gettysburg, the North's elite's were organizing regattas, as if there wasn't a care in the world.

* * * * *

The Annual Regatta of the Jersey City Yacht Club came off Tuesday afternoon, at 1 o'clock, from McGiehan's Basin, foot of Van Vorst-street, a large number of spectators being present.

– NYT, 6/25/1863

A meeting of the owners of yachts of the New- York Yacht Club, called by order of the

Commodore, was held at the office of the Secretary on Wednesday, 17th, Vice-Commodore A.C. KINGSLAND, presiding. The object of the meeting was to propose that the squadron rendezvous at Sandy Hook, for five or six days, for the purpose of fleet manoeuvering and trials of speed between the different yachts upon the ocean, up to Raritan Bay or toward the Narrows, anchoring each night in the Horse-shoe.

NEW-YORK VS. WILLOW, OF BROOKLYN.

The second elevens of the above clubs played a very interesting match on Saturday, on theground of the New-York club, Hoboken.

RUNNING RACKS AT CENTREVILLE COURSE, L. I. -- These races will commence to-day,

(Tuesday,) under the management of that well-known turf patron, Capt. THOMAS G. MOORE,of Kentucky, the owner of Idlewild and other fast horses, now at his racing stables adjoining the course.

-- NYT, 6/23/1863

The Sixth Annual Regatta of the Brooklyn Yacht Club, which came off yesterday, was a complete success both numerically and pecuniarily.

According to previous arrangements, the fast and commodious steamer Rip Van Winkle was at De Forrest's wharf, near Fulton Ferry, to receive the members and invited guests. Only a limited number of tickets was issued, but by some way or other at least seven or eight hundred people were on board.

On the way down, the hours were enlivened by Sanger's band, which discoursed some choice music. Several dances were improvised, and all had a good time generally. A glee club, composed of some 10 or 12 marines from the North Carolina, sang a number of patriotic and popular airs, much to the edification of the passengers.

-- NYT, 6/26/1863

To-day, it the circumstances of wind and weather permit. Divine services will be held on one of the larger yachts, and all things being made snug, the yachtsmen will lay by for the morrow, when, as is indicated elsewhere, they will have their grand Neptunical race, will show off and establish the points of their craft, will attempt time that will startle the old fashioned time-table, and do their best to have, under the standing regulations of the New-York Yacht Club, a jolly good time, coming home sun- burnt, freckled, tanned, wad with rousing appetites. -- 6/28/1863

The Annual Regatta of the New-York Yacht Club will come off on Thursday morning, the 11th of June, at half-past ten o'clock. There will be three prizes, valued at $150 each, which will be awarded to the first three yachts returning to the staks-boat abreast of the Club House, Hoboken.

Yachts allowed to carry men as follows: Schooners, first-class, one to every four tons of her measurement. Second class, one to every three and a half tons. Sloops, first-class, one to every three and a half tons; second class, one to every three tons. Every yacht under fifty tons shall carry, during a regatta, a serviceable boat not less than ten feet in length; and yachts over fifty tons shall carry one not less than twelve feet in length."

– NYT, 6/7/1863

At the City Regatta, to-day, HAMMILL won the first prize of $100 in the single scull race,

beating STEVENS, of Poughkeepsie – NYT, Boston, 7/4/1863

HAMMILL, WARD.

morning, an Albany gentleman offered to bet $800 even on HAMMILL., and was snapped up by a Poughkeepsian; and we had it for a fact that Mr. FLEMING had deposited $20,000 in the banks, a great portion of which he invested on HAMMILE. The crowds on the docks and in the steamboat hotel were immense, two propellers having come from Newburgh loaded with passengers, and a small one from Cornwall with WARD and his immediate friends. He lives, and trained himself at Cornwall, which accounts for his fine condition.

JOSHUA WARD is 6 feet high, 28 years old, and weight 104 pounds; he pulls a long, steady

stroke, which is considered best for a lasting race. His boat -- Dick Risden, of New-York – was built by GEORGE SHAW, of Newburgh, of mahogany; 29 1/2 feet long, 17 inches beam, and weighs 45 pounds.

HAMMILL is 5 feet 7 1/8 inches high, about 24 years old, and weighs 153 pounds. He pulls a

short, quick stroke, which, with a rippled water and his narrow boat, might have been anadvantage to him, but the water in this race was as smooth as glass.

Mr. ROBERTS, the President, and Mr. COTTE, the Treasurer, begged our reporter to announce that early in the Fall they will give a grand four-oared boat race, and hope boatmen will prepare accordingly against the announcement is publicly made.

-- NYT, 7/24/1863Thursday, August 8, 2013

The Tire King of Long Island

My grandmother liked to announce to her friends that her oldest son was going to be a priest and her youngest a doctor. This was fine with my father until he was old enough to notice girls. He started to get very uneasy about disappointing his mother, who was, shall we say, formidable. Then came the party for the sons of a friend who were young Jesuits bound for the missions in the Philippines. It was a proud day for the Carnegie Hill Catholics, young men marching off to do the work of Christ. Grandmother introduced my father and his brother to the young Jesuits with her routine introduction: "This is Tom, my youngest son. He is attending Notre Dame and is going to be a doctor. This is Jim, my oldest son. He attends Holy Cross and is going to be a priest." The Jesuit abruptly interrupted her. Something only a Jesuit would dare to do. Something only a Jesuit could survive. "Eleanor, the vocation to be a priest is the boy's decision and the boy's decision alone." My father gave a silent prayer of thanksgiving. My grandmother never said another word about the priesthood. Perhaps if there'd been more Jesuits around to counsel ardent Catholic mother's the Church would have had less trouble with priests who chose the wrong vocation.

Jobs were hard to find during the Depression. My father found one working in a garage pumping gas and fixing flat tires. He worked out a way to change a flat truck tire in 5 minutes when it usually took 30. He was happy working with his hands. His mother wasn't. One day she announced you're starting at Fordham Law School next week. I never applied to any law school. I've taken care of it. My father said he was never happy as a lawyer. "Who knows, if I'd have stood up to mother, I might have been the Tire King of Long Island."

Jobs were hard to find during the Depression. My father found one working in a garage pumping gas and fixing flat tires. He worked out a way to change a flat truck tire in 5 minutes when it usually took 30. He was happy working with his hands. His mother wasn't. One day she announced you're starting at Fordham Law School next week. I never applied to any law school. I've taken care of it. My father said he was never happy as a lawyer. "Who knows, if I'd have stood up to mother, I might have been the Tire King of Long Island."

Don't Join the Army Son

No they never taught us what was real

Iron and coke

And chromium steel.

When I turned 18 and became eligible for the draft, my grandmother who was aloof to say the least looked me in the eye and said: "Don't join the Army, son. They'll use you for cannon fodder."

Never mind Tammany Hall. The most powerful political constituencies in New York City were women's clubs like the Catholic Daughters of America. St. Patrick's Cathedral was built by the pennies and nickels of Irish servant women. The Jesuits' opulent St. Ignatius Loyola Church at Carnegie Hill was built by and for Catholic women whose mothers may have been cleaning women, but whose fathers had been wildly successfully in the iron business and played poker with JP Morgan and Andy Carnegie. (Carnegie was a Gaelic speaker, by the way) The Sacred Heart sisters educated the daughters of the most successful. After Otto Kahn died the elegant sisters set up shop in his mansion, Palazzo Della Cancellaria style (Papal Chancellery). The Kennedys and Mara (as in football Giants) weren’t even on the social radar for women like my grandmother. If they were acknowledged at all, it was: Kennedy the rum runner, Mara the bookmaker.

The women's political power rested on three pillars: votes, money, and the prestige of the Union army. Ellen Ewing Sherman was Queen Bee in the New York City after the Civil War. She was as ardent a Catholic as they come. How could Mrs. Astor refuse an invitation or request to donate to Irish relief from the wife of General William Tecumseh Sherman? The general resided in New York City after the Civil War until his death in 1891. These days the New York Times feigns complete bewilderment when it’s accused of being anti-Catholic. What totally and permanently pissed off New York’s Catholic women was The Times stationing a reporter outside the door of the Sherman house while the general was dying. Incredibly they were on the lookout for the comings and goings of Catholic priests. When they caught one, The Times published the “sordid” revelation that the great general had been given the last rites of the Catholic Church (certainly against his will), creating a minor scandal. Sherman’s brother had to publicly explain to The Times that, although Sherman wasn’t a Catholic Christian (just baptized and married so), Catholic sacraments were welcomed by the general because they greatly comforted his family.

While many New Yorkers like to march with the original Fighting Irish, the 69th New York Infantry (aka, the Irish Brigade), my grandmother and her friends wouldn't have been caught dead anywhere near a St. Patrick's Day parade. When she was a young girl, the old pirate Dan Sickles still hopped up and down 5th Avenue, a living testament to the horrors of war. Sickles, who'd been married to the “natural” daughter of Mozart's librettist by Archbishop Hughes, had had his leg blown off by a cannonball at Gettysburg leading the city's famous Excelsior Brigade. Sickles life playbook was Mozart’s Cosi Fan Tutte farce about soldiers and fiancé swapping. After philanderer Sickles shot his wife’s lover, his attorney Thomas Meagher, ’48 rebel and Irish Brigade commander, got him acquitted of murder based on a plea of temporary insanity. Sickles, in the end, didn't leave his wife and remained within the Pale. His funeral at St. Patrick's was attended by thousands.

Iron and coke

And chromium steel.

When I turned 18 and became eligible for the draft, my grandmother who was aloof to say the least looked me in the eye and said: "Don't join the Army, son. They'll use you for cannon fodder."

Never mind Tammany Hall. The most powerful political constituencies in New York City were women's clubs like the Catholic Daughters of America. St. Patrick's Cathedral was built by the pennies and nickels of Irish servant women. The Jesuits' opulent St. Ignatius Loyola Church at Carnegie Hill was built by and for Catholic women whose mothers may have been cleaning women, but whose fathers had been wildly successfully in the iron business and played poker with JP Morgan and Andy Carnegie. (Carnegie was a Gaelic speaker, by the way) The Sacred Heart sisters educated the daughters of the most successful. After Otto Kahn died the elegant sisters set up shop in his mansion, Palazzo Della Cancellaria style (Papal Chancellery). The Kennedys and Mara (as in football Giants) weren’t even on the social radar for women like my grandmother. If they were acknowledged at all, it was: Kennedy the rum runner, Mara the bookmaker.

The women's political power rested on three pillars: votes, money, and the prestige of the Union army. Ellen Ewing Sherman was Queen Bee in the New York City after the Civil War. She was as ardent a Catholic as they come. How could Mrs. Astor refuse an invitation or request to donate to Irish relief from the wife of General William Tecumseh Sherman? The general resided in New York City after the Civil War until his death in 1891. These days the New York Times feigns complete bewilderment when it’s accused of being anti-Catholic. What totally and permanently pissed off New York’s Catholic women was The Times stationing a reporter outside the door of the Sherman house while the general was dying. Incredibly they were on the lookout for the comings and goings of Catholic priests. When they caught one, The Times published the “sordid” revelation that the great general had been given the last rites of the Catholic Church (certainly against his will), creating a minor scandal. Sherman’s brother had to publicly explain to The Times that, although Sherman wasn’t a Catholic Christian (just baptized and married so), Catholic sacraments were welcomed by the general because they greatly comforted his family.

The women had their own priorities. It wasn't accepting "gratuities" that ended my grandfather's good friend Jimmy Walker's political career. It was taking up with showgirl Betty Compton and publicly leaving and divorcing his wife that was the end of Jimmy. In the category of strange but true, you’ll find Representative Joseph Gavagan addressing the Catholic Daughters of America on why the Bible had to be kept out of the public schools: the King James Bible is a Protestant plot to seduce Catholic children. Crazy as it sounds this was a hot topic for Catholic women in the 1930s because even into the 1960s the old Irish were telling stories about per-Civil War New York when the city nearly went up in flames over whose Bible, if any, would be taught in the public schools.

While many New Yorkers like to march with the original Fighting Irish, the 69th New York Infantry (aka, the Irish Brigade), my grandmother and her friends wouldn't have been caught dead anywhere near a St. Patrick's Day parade. When she was a young girl, the old pirate Dan Sickles still hopped up and down 5th Avenue, a living testament to the horrors of war. Sickles, who'd been married to the “natural” daughter of Mozart's librettist by Archbishop Hughes, had had his leg blown off by a cannonball at Gettysburg leading the city's famous Excelsior Brigade. Sickles life playbook was Mozart’s Cosi Fan Tutte farce about soldiers and fiancé swapping. After philanderer Sickles shot his wife’s lover, his attorney Thomas Meagher, ’48 rebel and Irish Brigade commander, got him acquitted of murder based on a plea of temporary insanity. Sickles, in the end, didn't leave his wife and remained within the Pale. His funeral at St. Patrick's was attended by thousands.

My grandmother came of age when even more of the Fighting Irish were maimed and died, in what was a savage, bewildering, utterly pointless First World War. Two generations later and yet another war, the child who nestled against her bosom in a taxi on a rainy night ride up 5th Avenue was ready to be drafted. Would Tiffany mosaics and the Carrara marble of St. Ignatius Loyola Church be of any comfort when she was wearing black again?

In 1969 anti-war demonstrations led by the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) broke out at Holy Cross College, the Massachusetts outpost of New York’s Irish. Black students led by Supreme Court Justice to-be Clarence Thomas staged a walkout. Charles Horgan who was the head of the Holy Cross trustees told the college president he’d support him in whatever decision he made regarding disciplining the black students and the SDS. Horgan was also the law partner of Felix Muldoon, the Democratic lieutenant who'd told Flynn to back Roosevelt in 1932: "we need a Dutchman not a Catholic [Smith] to deliver our message." Muldoon was the husband of my grandmother's friend from her schoolgirl days with the Sacred Heart sisters, the formidable (ferocious) Agnes Muldoon. Two birds were on Horgan's shoulder when he was advising the college president on how to deal with Thomas. He didn't need to tell the Holy Cross president what they were.

#1. "We've worked long and hard to pry the Black vote out of the Republican grasp. Don't screw this up."

#2. "The friends of Agnes Muldoon want to send a message about the war. Your SDS aren't the only ones who want to use the Blacks to deliver it. For God's sake save me from Agnes Muldoon!"

#1. "We've worked long and hard to pry the Black vote out of the Republican grasp. Don't screw this up."

#2. "The friends of Agnes Muldoon want to send a message about the war. Your SDS aren't the only ones who want to use the Blacks to deliver it. For God's sake save me from Agnes Muldoon!"

The King James Bible and the Story of American Freedom

Bowdlerizing the King James Bible:

In a New York Times story about the 400th anniversary of the Bible's translation into English, Edward Rothstein concludes by invoking Winston Churchill who wrote about

'"English-speaking peoples,' and their distinctive perspective on the world. Could some of this be traced to the heritage of the King James Bible, including emphasis on individual liberty and responsibility?"

Mr. Rothstein neglected to note the unique place of King James Bible in the story of American freedom. The first objection to use of the Bible in America's public schools, occurred in 1840s New York City, when Catholic immigrants strongly objected to use of the King James Bible for instruction of Catholic children in city's public schools. America's largest Christian denomination does not use the King James Bible produced by the British, and stubbornly resisted forced assimilation into Anglo-Saxon Protestantism via the public schools.

Others using more overtly racist language than Churchill invoked older pre-Christian, tribal roots.

http://hidden-civil-war.blogspot.com/2014/01/anglo-german-exceptionalism.html

'"English-speaking peoples,' and their distinctive perspective on the world. Could some of this be traced to the heritage of the King James Bible, including emphasis on individual liberty and responsibility?"

Mr. Rothstein neglected to note the unique place of King James Bible in the story of American freedom. The first objection to use of the Bible in America's public schools, occurred in 1840s New York City, when Catholic immigrants strongly objected to use of the King James Bible for instruction of Catholic children in city's public schools. America's largest Christian denomination does not use the King James Bible produced by the British, and stubbornly resisted forced assimilation into Anglo-Saxon Protestantism via the public schools.

Others using more overtly racist language than Churchill invoked older pre-Christian, tribal roots.

http://hidden-civil-war.blogspot.com/2014/01/anglo-german-exceptionalism.html

The Black Legend

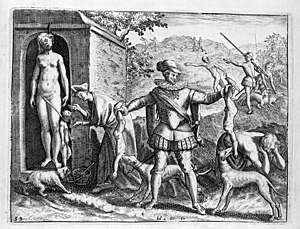

|

| 1598 engraving by de Bry depicting a Spaniard feeding Indian children to his dogs, characteristic of the anti-Spanish propaganda that originated as a result of the Eighty Years' War. |

Cousin to the Black Legend is Whig History, Anglo-German triumphalist history that celebrates the successes of Anglo republicanism, e.g., abolition, while ignoring it's sins, e.g., the proto-Apartheid Penal Laws imposed on the Irish, leading to the Famine tragedy, Britain's opium wars, and the Nativist roots of the American Republican Party.

Nessun Dorma: The Fighting Irish Assault the Stone Wall on the 13th of December 1862

Fredericksburg?

Where is Fredericksburg?

The bloody wound of New York's Irish

Men

writing their names on pieces of paper

pinning the papers to their uniforms

with the simple hope

of escaping an unmarked grave

Boys

sleepless in the darkness

each wondering if the dawn will bring

the worst day in his poor mother's life

The six desperate charges

the bodies which lie in dense masses...

"Never at Fontenoy, Albuera or Waterloo

was more undaunted courage displayed"

than at Fredericksburg

the cruel stone wall where New York's Irish Brigade died.

The requiem at St. Patrick's

the call for the widows to come forward

and be cared for...

Fredericksburg!

Fredericksburg!

Fredericksburg!

The Pennsylvanian's chanting

and waving their green banner

the Harp and the Sunburst

over Pickett's troops

who have fallen before them

at yet another cruel stonewall

Gettysburg.

Where is Fredericksburg?

The bloody wound of New York's Irish

Men

writing their names on pieces of paper

pinning the papers to their uniforms

with the simple hope

of escaping an unmarked grave

Boys

sleepless in the darkness

each wondering if the dawn will bring

the worst day in his poor mother's life

The six desperate charges

the bodies which lie in dense masses...

"Never at Fontenoy, Albuera or Waterloo

was more undaunted courage displayed"

than at Fredericksburg

the cruel stone wall where New York's Irish Brigade died.

The requiem at St. Patrick's

the call for the widows to come forward

and be cared for...

Fredericksburg!

Fredericksburg!

Fredericksburg!

The Pennsylvanian's chanting

and waving their green banner

the Harp and the Sunburst

over Pickett's troops

who have fallen before them

at yet another cruel stonewall

Gettysburg.

Sotomayor: Daughter of the American Revolution

Daughter of the American Revolution? The biography of Supreme Court Associate Justice Sandra Sotomayor may not be quite complete. It is well-known that the American Revolution was a trans-Atlantic war. Our French allies sent troops to Rhode Island and Virginia, notably the Siege of Yorktown. John Paul Jones took the war to Britain's home waters. Little remembered, though, is the Siege of Gibraltar, which was the largest battle of the war in terms of land and sea power, pinning down significant portions of the British army and navy in Spain. The commander of America's French and Spanish allies in this battle was Martin Alvarez de Sotomayor.

Strictly speaking, this has nothing to do with America's Civil War, but it's a really fun thought about America's debt to Spain and the Spanish.

Strictly speaking, this has nothing to do with America's Civil War, but it's a really fun thought about America's debt to Spain and the Spanish.

Trinity Church and the United Irishmen

The idea of a Catholic Church in New York City at first was not welcome in some prominent circles. However, when the Catholics asked New York City's Common Council for a site to build a church, Trinity Church volunteered to lease the Catholics some of their real estate. Later Trinity cancelled all back rents and transferred title to the Catholics for the land where St. Peter's, the oldest Roman Catholic Church in New York City, was built. St. Paul's Chapel of Trinity Parish is home to memorials to the old friends and patriots of the United Irish movement Addis Emmet, a New York Attorney General, and Dr. William MacNeven, the devout Catholic who fought NYC's cholera epidemics and published theories on atomic structure. I hope this gives new meaning to the expression "The Irish Never Forget."

----------------------

The United Irishmen and New York City

http://www.libraryireland.com/IrishSettlers/AppendixVI.php

----------------------

The United Irishmen and New York City

http://www.libraryireland.com/IrishSettlers/AppendixVI.php

The Great Militia Mobilization of June, 1863

(and Richard S. Ewell Ultramarathon)

“Separated from Hellas by more than a thousand miles, they had not even a guide to point the way.”

― Xenophon, Anabasis

“Separated from Hellas by more than a thousand miles, they had not even a guide to point the way.”

― Xenophon, Anabasis

|

| Thálatta! Thálatta! |

Pennsylvania’s Cumberland Valley and the nearby land west of the Susquehanna River is one of the most bountiful regions in the United States, and in 1863 it was virtually undefended. At the valley’s north end, no one guarded Harrisburg, the state capital, or the vital Susquehanna bridges, including the Rockville Bridge carrying the Pennsylvania Railroad to Ohio and Pittsburgh’s Allegheny Arsenal and Fort Pitt Foundry.

In the spring of 1863 the Confederacy was in crisis. Despite a magnificent victory at Chancellorsville, Robert E. Lee’s army was starving and Lee’s soldiers were beginning to fall ill with the disease of malnutrition: scurvy. In the West, Ulysses Grant’s grand maneuver had placed the Confederacy’s last bastion on the Mississippi, Vicksburg, under siege.

The crisis at Vicksburg seemed to dictate that Lee send reinforcements from Virginia to break the siege and drive Grant back to Missouri. But Pennsylvania beckoned.

“Carrying the war into the heart of the enemy’s country is the surest plan of making him share its burdens and foiling his plans.”

-- Dennis Hart Mahan, West Point Professor of Engineering and the Art of War

Perhaps it was at West Point, while superintendent in the 1850s, that Lee became a disciple of Napoleon and the dashing French tactics studied in Professor Dennis Hart Mahan’s Napoleon Club (seminar like meetings held for the base officers and some senior cadets). Pennsylvania beckoned. The Shenandoah Valley beckoned, the perfect avenue for the grand Napoleonic stroke: the Manoeuvre Sur Les Derrieres. The Sirens beckoned: Ulm, Jena, Eylau, Wagram, Smolensk. Lee argued that instead of reinforcing Vicksburg he could invade Pennsylvania, capture mountains of food for his army, destroy the strategic bridges on the Susquehanna, and lure the Union army into the open where he would destroy it. Vicksburg was Grant’s Smolensk: Lee would not be outdone. Someone should have stuffed beeswax in Jefferson Davis’s ears, or at least reminded Lee and Davis that Smolensk and Napoleon’s other victories led to Moscow, death in the Russian winter, and Waterloo, on a battlefield remarkably similar to Gettysburg. On June 3, 1863 the Army of Virginia began its march north. The Blue Ridge and South Mountain on the eastern border of the Shenandoah and Cumberland valleys shielded Lee from detection and attack, but also blinded him to his enemy’s movements. With hubris, the prideful arrogance of classical mythology, Lee’s 1863 tragedy began, his clear Napoleonic vision engulfed in the fog of war and miscalculation. Pennsylvania began to buzz with defenders.

“You First My Dear Gaston!” “After You My Dear Alphonse!”

It is hard to grasp today that the bickering between the Republican Secretary of War and the Republican governor of Pennsylvania over who would call out the Pennsylvania state militia would be the prequel to a 1900 comic strip about two bumbling, overly polite Frenchmen.

In late 1862, General Major Robert Schenck relieved General Wool as commander of the Middle Department, which was responsible for guarding the long frontier between Ohio and Delaware. Schenck took command even though he’d been wounded at Second Bull Run and was permanently disabled. The Middle Department held two key strong points in the Shenandoah Valley at Winchester and Harpers Ferry. Whatever the good intentions of stationing troops in the Shenandoah, the practical effect of these Union garrisons was to supply the Confederate army with arms and ammunition. When Winchester’s commander Robert Milroy ignored Schenck’s order to withdraw to Harper’s Ferry (an order that neglected to mention the approaching Confederate tsunami), Lee steamrolled Milroy’s hapless division and then bypassed Harper’s Ferry (June 12 to 15).

On June 10th, after discovering the Confederates were on the move and realizing Schenck’s responsibilities were too broad, the War of Department established a Department of the Monongahela at Pittsburgh and a Department of the Susquehanna at Harrisburg, Major General Darius Couch commanding the later. The War Department thought a big cavalry raid was headed for Pittsburgh and established Couch’s command to placate Pennsylvania’s Governor Andrew Curtain who thought Lee was headed for Harrisburg, the state capital. Couch had virtually no troops and, although he was promised supplies from government depots and arsenals, he was told “Federal funds could not be used to pay militia that had not been mustered into the service of the United States.” The Pennsylvania militia, like that of every other state except New York, existed only on paper so paying militia soldiers was the least of Couch and Curtain’s problems.

On June 12th Governor Curtain and General Couch conferred on how to raise troops. With the grudging concurrence of Couch, Curtain telegraphed Washington and requested that recruiting for 3-year volunteer units be stopped and recruits diverted to Couch’s command. Secretary of War Stanton immediately denied the request and in a separate telegram rebuked Couch. Curtain then issued a proclamation “inviting” the attention of the people of Pennsylvania to Couch’s orders to enlist volunteers. Volunteers would serve until the end of the war, promised pay when Congress got around to appropriating money for it. Very few Pennsylvanians volunteered. By the 13th Couch and Curtain were receiving reports that Winchester was under heavy attack. Curtain wanted to call out the (nonexistent) state militia, but was on unpopular political ground and did not know if he had the authority since the tsunami hadn’t hit Pennsylvania, yet. Curtain wired General-in-Chief Halleck asking if, under direction of the President, he should call out the militia. Halleck wired back curtly for Curtain to go through military channels. Curtain then wired Stanton: “The President should authorize the Governor to call out the militia today.” Stanton replied: “Has not the Governor the right, under your state laws and constitution to call out the militia of the State whenever he deems it necessary to do so? This Department has no objection to his doing so.” By the 14th Stanton realized the invasion was headed for Harrisburg and so informed Couch and Curtain. Stanton began to send Couch some experienced officers and a few volunteers started to appear, very few.

Curtain and his advisors were desperately looking for cover to call out the (nonexistent) Pennsylvania militia. They sent Couch’s most trusted aide, Colonel Thomas Scott, to Washington to ask the President to order Curtain to call out the militia. After proposing this to Stanton and the Solicitor General, Scott was told “that the plan was illegal; the law expressly forbade the President to issue such an order to any state. Lincoln could…request the governors of the several states to furnish men to serve for six months or more, in view of the threatened invasion.” On June 15th, Lincoln issued a proclamation calling for 100,000 volunteers. Curtain followed with his own proclamation for 50,000 volunteers to fill the Pennsylvania quota. Still virtually no volunteers.

HARRISBURGH, Penn., June 16.

To the People of Philadelphia:

…Yesterday, under the Proclamation of the President, the militia were called out. To-day a new and pressing invitation has been given to furnish men to repel the invasion. Philadelphia has not responded; meanwhile, the enemy is six miles this side of Chambersburgh, and advancing rapidly….

-- A.G. CURTIN. (reported in New York Times)

To the People of Philadelphia:

…Yesterday, under the Proclamation of the President, the militia were called out. To-day a new and pressing invitation has been given to furnish men to repel the invasion. Philadelphia has not responded; meanwhile, the enemy is six miles this side of Chambersburgh, and advancing rapidly….

-- A.G. CURTIN. (reported in New York Times)

The six month commitment was a show stopper. Curtain and Stanton continued to bicker over the term of service. Finally on June 17th, Stanton gave in: “Let them be called upon to muster under the President’s call. If they refuse, then muster them whichever way you can… [however, Stanton] refused to issue anything [supplies and equipment] to any troops not Federalized.” 8,000 men from the cities, mines and farms of Pennsylvania began to take up arms for the duration of the emergency, headed for the railroad depots and the militia camps at Harrisburg.

By late June 15th, Ewell’s Corps was near the Potomac at the southern end of the Cumberland Valley and Ewell’s cavalry screen had captured Chambersburg in Pennsylvania, only 50 miles short of Harrisburg. Confederate foraging parties looted the Cumberland’s bounty, grain, livestock, anything that moved, and marched it south. They burned all the railroad equipment and bridges in their path. In one of the war’s worst atrocities, African-Americans were rounded up and marched south along with the captured livestock, escaped slave or not. At this point Ewell’s cavalry screen, Jenkins’ brigade, could have captured Harrisburg without a fight. Instead, the inveterately timid Jenkins mistook a crowd of spectators for the Union army, panicked, evacuated Chambersburg and retreated back toward the safety of Ewell’s infantry.

McClellan is on the way with 40,000 Troops!

This was the tall tale farmer D.K. Appenzellar told the Confederates when they returned to Chambersburg later in June causing the ever timid Jenkins and Rodes’ division to deploy for combat when a small company of Union cavalry appeared on the horizon. It was not, however, far from the truth.

Democratic Governor Horatio Seymour had spent the spring quarreling with the Lincoln administration over the draft and New York State’s quota, but he immediately said “YES” to Lincoln’s call for emergency volunteers.

The New York State militia unlike that of the other states was a real, functioning organization, not just a statute on paper. It had generals, armories, weapons, uniforms and soldiers. It’s famous “Silk Stocking” 7th Regiment and “Fighting Irish” 69th had been among the first units to arrive to defend Washington and Lincoln in 1861. New York militia units commanded by William Tecumseh Sherman had fought at Bull Run. Seymour put George McClellan a former railroad executive and until recently commander of the Army of the Potomac in charge of the mobilization. Most of the New York State militia units were in New York City and Brooklyn. Within two days of Lincoln’s call on June 15th, New York regiments were on their way by rail to Harrisburg and they would keep coming until over 12,000 had reached the city’s defenses. In total New York State sent 27 regiments to the defense of Pennsylvania and Maryland. 20 of the regiments came from New York City and Brooklyn. McClellan, however, never crossed the Hudson with them.

The noble response of the New-York State Militia of this City to the call for troops to meet the pressing emergency in Maryland and Pennsylvania, was exemplified yesterday by the departure of no less than three regiments -- the Thirty-seventh, Twenth-second, and Eleventh, making six regiments in two days.

– New York Times, June 19, 1863

Three more regiments left the City yesterday for the seat of war, making twelve in all, since the present emergency -- the Sixth and Sixty-ninth militia, and the One Hundred and Seventy-eighth Volunteers…. The men carry with them two days' rations, and from their soldier like appearance and determined looks, there is no doubt but when they attach themselves to the great army at Harrisburgh, and take the field to meet the foe, they will nobly sustain the Irish character for indomitable courage….."Are you Irishmen or Germans?" "Neither," was the noble response of the Captain of Company K, "we are all Americans."

– New York Times, June 23, 1863

There were no departures of City military regiments yesterday. The Tenth and Fifty-fifth are rapidly filling up, and will leave soon. Recruiting for the volunteers is quite brisk, and many of the returned soldiers are reenlisting [two year volunteers whose enlistments had just expired].

– New York Times, June 24, 1863

Except for a small contingent from New Jersey, no other state sent militia to aid Pennsylvania.

– New York Times, June 24, 1863

Except for a small contingent from New Jersey, no other state sent militia to aid Pennsylvania.

“After you, Alphonse” “No, Gaston, after you.” – Round Two

The first and probably only African American to die in combat during the Gettysburg campaign was decapitated by a Confederate artillery shell in the trenches defending the Wrightsville Bridge on the Susquehanna. Predictably Curtain and Stanton bickered over who would take the blame for granting that tragic distinction to an unknown member of the 27th Pennsylvania Militia.

The most enthusiastic response to Governor Curtain’s call to arms came from Pennsylvania’s African Americans, but when offered African American units, Curtain demurred. He issued a proclamation refusing to accept these units unless authorized by the War Department. When Captain William Babe appeared, anyway, at Harrisburg with an African America company raised at Philadelphia they were ingloriously sent home by Couch. The Confederates were closing in on Harrisburg. “On the 18th, Stanton authorized Couch to receive any volunteer units, without regard to color [Stanton no doubt concluding it was now pointless to tell Curtain that Curtain was in command of the Pennsylvania militia].”

Before closing this report, justice compels me to make mention of the excellent conduct of the company of Negroes from Columbia. After working industriously in the rifle-pits all day, when the fight commenced they took their guns and stood up to their work bravely.

- Colonel Jacob Frick, after action report, defense of the Wrightsville Bridge (in Paradis)

The Horny-Handed Sons of Toil

Thousands of Pennsylvania and New York militia were crowding Harrisburg. Some even knew how to load and fire a musket. Couch was busy teaching the rest which end of a musket was which. The missing ingredient was combat engineers, the people who build fortifications. The War Department sent engineering officers from West Point to supervise construction, but the militia troops assigned to dig the rifle pits (entrenchments) and artillery platforms were soon blistered, bloodied and exhausted.